I will occasionally, in this space, post stories from my book, MY LIFE IN SHORT FORM.

——————————————————

CHRISTMAS EVE REMINISCENCES…

From the book – “MY LIFE IN SHORT FORM”

I am sitting here tonight with a sense of completeness. All our adult children have returned home for the holidays, and now everyone except for me has headed off to bed. I am left here, bathed in the light of our Christmas tree, and my mind has stepped inside a time machine. I am drifting back to the Christmases I remember growing up in King’s Point.

We didn’t have much in the way of possessions, but I don’t remember any time when I did not feel like I had everything I needed. Until I was nearly a teenager, I lived in a house without electricity, central heat, or indoor plumbing. Our drinking water was fetched from a spring up behind my Uncle Jack’s house. We filled the water barrel by lugging galvanized buckets from the well, along several hundred metres of the corduroy lane. Bringing full buckets without spilling the contents was not easy; the containers would constantly bang against our legs and after a few steps, the contents would slosh onto our pants and spill into our boots. To steady the pails, my father made yokes to limit the loss of the precious liquid. The contraption was basically a square frame made from one-inch strips of lumber from our sawmill. The frame would be placed on top of the two buckets and when they were lifted, the yoke kept the containers from coming close to our bodies and kept the pails steady.

Even without all the conveniences, Christmas was a special time for us, and I can’t recall us ever getting any big expensive gifts. The stockings we hung were nothing exceptional. Mom would always take the largest worsted sock we owned and wash it until it passed the Santa cleanliness test. They were hung where we figured they would easily be found by the jolly elf, and since our house never had a fireplace, the stockings were hung somewhere near the woodstove. We were told that Santa came down our stovepipe and somehow, managed to extricate himself from the cast iron enclosure, and fill the socks with goodies.

Christmas eve was always full of anticipation. Dad would listen to our old RCA tube radio for the first sign that Santa was on his way. Back on December 24, 1955, NORAD started tracking Santa, and on Christmas eve, our father would always have his ear cocked to the radio, relaying Saint Nick’s progress as he headed south. At what was obviously a predetermined time, my brothers and I were sent off to bed full of adrenaline and our hearts racing. I shared a bedroom with three of my brothers, and I slept on the top bed of one of the two sets of bunk beds.

On Christmas morning, I was usually roused by an older brother announcing that our stockings had been magically filled with goodies. All of us, still in our long johns, raced to the wood stove. Once there, we’d dive into those wool stockings to find out if Santa had deemed us naughty or nice.

The items left in our stockings would not be considered much of a treat today: we’d always receive an apple and sometimes we’d even get an orange. Unlike now, oranges were actually a rare treat back then—especially in winter. Occasionally we’d get a small clementine. I don’t know how they arrived all the way from Morocco, but somehow it happened around Christmas each year. Other items found inside our sock would include a few white peppermint candies (the ones with the pink stripes), several jawbreakers (the kind that kept changing colours as you sucked them), and sometimes a nickel or dime in the toe.

By the time our treasures were revealed, Mom would have a hearty breakfast on the table. We didn’t have a great grocery store in King’s Point, but what we couldn’t get in a store, my parents grew, fished, or hunted. On those Christmas mornings, nobody could have convinced me we weren’t the wealthiest people on earth. The first meal of the day almost always consisted of fresh eggs. Sometimes it would include fisherman’s brewis fried up in rendered pork scrunchions…not a kid favourite, but the adults seemed to relish it.

After we devoured the brewis, bacon and eggs, and fresh bread toasted atop the kindling drying in the oven, we’d all make a beeline for the Christmas tree. It was never an exorbitant affair, but the tree was always a freshly cut fir or spruce, and the decorations were nearly always old glass bulbs, handed down from generations past, or trinkets handmade by family members. The smell of the fresh evergreen mixed with the hint of wood smoke coming from our cast- iron stove still lingers in my mind today.

Our gifts at Christmas were almost always practical. It was a rare treat when we received anything we didn’t expressly “need.” Usually, I was inundated with home-knit socks and mitts. I cringed every time I opened a gift and found something practical. I was a child who couldn’t care less about homemade presents. What I wanted were the things I saw in the Eaton’s catalogue—like that Daisy BB gun or the six-shooter cap gun—not another pair of worsted mitts.

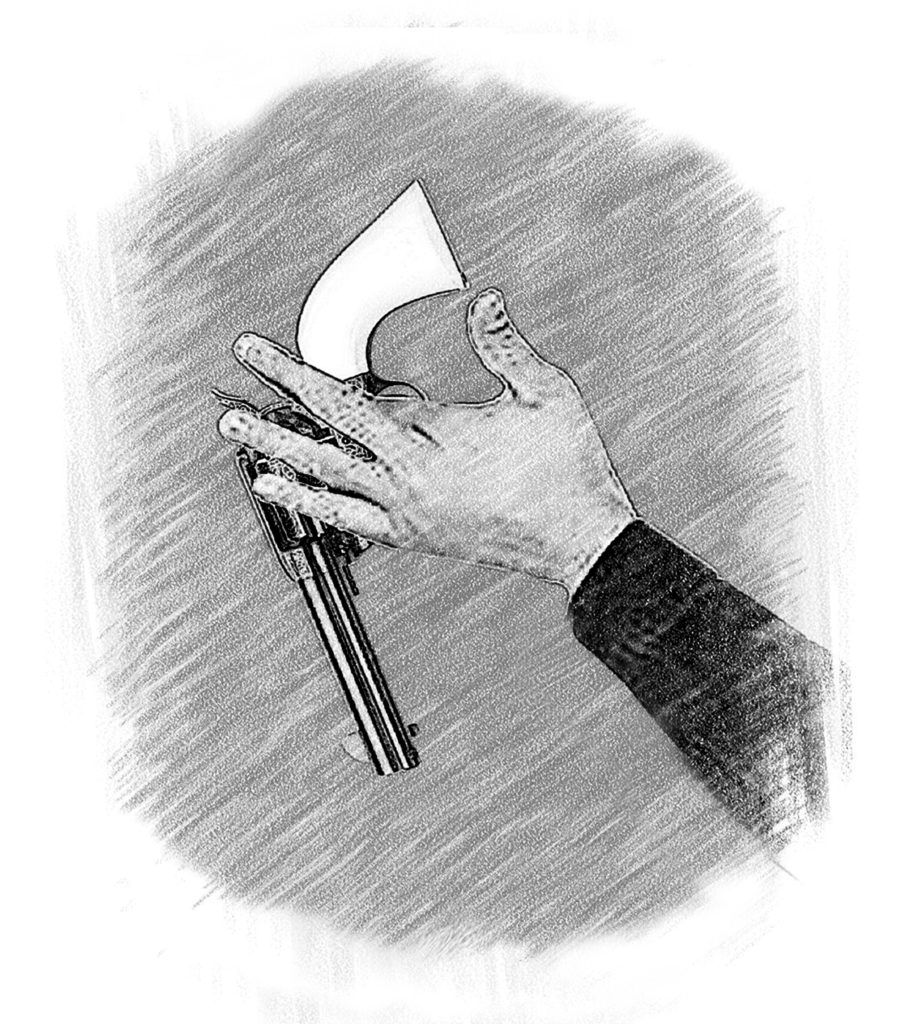

Of all the Christmas mornings, none is more vivid than the day that Santa finally delivered a gun and holster to me. It was one I’d been looking at and loudly commenting on for months. The price of the two-holster set was $4.99 and the single-sidearm set was $3.99. I had cut the picture out of the catalogue and would pull it from my pocket every time I encountered anyone who showed even the faintest interest. I never dreamed such a special gift would be bestowed upon me, but that memorable morning I opened my present and there, inside the small gift box, was the single-holster sidearm.

I immediately forgot anything else I received that day, or for that matter, any other Christmas. All I know is that I strapped on my gun belt and morphed instantly into Billy-The-Kid. I loaded up the chamber with a fresh roll of caps and ran outside into the cold December air to show my friends. The temperature was well below zero, but I didn’t care. At first, I heeded my mother’s suggestion of wearing homemade mittens with the specially knitted trigger finger. They were really designed for using a chainsaw but worked quite well for my six-shooter. Soon, though, I abandoned them for the natural feel of my index finger on the cold steel of the trigger. Without the cumbersome mitts, I was able to spin the handgun like my heroes in the old western movies.

As the day wore on and the four-o’clock dusk approached, I reluctantly came back to the warmth of the house, fingers frozen and my heart full of fire. I had become like the stars on the big screen—I was a gunslinger! For many months after Christmas, I wandered the roads of King’s Point, displaying my talents as the expert sharpshooter I had become. I have received many more wonderful gifts since that morning, but none stands out quite like the Colt 45 Santa brought that day.

How things have changed since that time. These days, nothing seems to be special anymore. The most fantastic gadgets are available at the click of a mouse and can be delivered to your door overnight. But, as everything we wish for becomes easily attainable, items have lost their special meaning. Now my attitude has undergone a complete 360: I can only hope to receive a gift as special as those made with the loving care of someone close to you. Mom, if I could have my time back, I would shower you with my thanks for all those wonderful pairs of knitted hand and foot coverings I received so long ago.

Buy this book at: www.amazon.ca

————————————————————

FUN WITH DICK AND JANE

On my first day of school, I skulked home at noon because I was sick. Well, I wasn’t really sick…I discovered I hated school on day one. It took me about a week to get used to the idea that I had to show up every day. Nobody had prepared me for prison life at such an early age.

We had two schools in King’s Point: the Salvation Army operated the one all my cousins attended, but because of our father’s little idiosyncrasies, my siblings and I ended up at the school run by the United Church. That was it for educational opportunities in King’s Point. Our school consisted of two rooms, each accommodating several grades. When I started, my classroom held students from grades one through five; the other room housed grades six to eleven. Back then, the schools in Newfoundland graduated students after grade eleven, and, for those who continued their education, Memorial University brought them up to speed with a “foundation year.”

I remember my first day of grade school vividly. Someone, I don’t recall who, took me by the hand and dragged me down the back road. I had nothing against education but it seemed unnecessary to do all my learning inside. The first bit wasn’t so bad because everyone was hanging outside playing. Glennis Noble said hi to me and I felt my face turn red. I ignored her and shuffled over to where Dudley Burt was kicking a soccer ball against the school wall. That’s when I heard a grating clatter that sent everyone running for the entrance: the bell. My first instinct was to run home, but I thought better of it after I imagined what I’d tell my mother when I got there. No…I figured I better give it a shot, so I mustered all my courage and got carried along with the crowd heading for the door. The first few minutes seemed to run fairly smoothly: the bustle of everyone removing their jackets and selecting their seats kept me distracted, but then my first real reservation about school reared its ugly head. Each seat had a desk attached to it and each desk sat two students…and they had seated me with a girl! I’m not sure how it was possible, but there was Glennis Noble again. Until then, I had not been around any girls other than my cousins Maxine and Stella. I hadn’t considered them girls…they were just part of our gang.

I didn’t last long that first day. I had a terrible stomach ache, and nobody had told me I should empty my bladder before starting class. I raised my hand, as I had been instructed, before asking permission to do anything. My arm was in the air for what seemed like an hour to no avail. Nature took its course, and I went home a couple of hours later with an embarrassing wet stain on my pants, vowing never to return.

That commitment of abstention lasted until the next morning, when I was once again taken by the hand and led off down the back road. I hadn’t given up my dream of delaying the inevitable, though, and that first week I cooked up an excuse to leave school early almost every day.

In my second week things seemed to level out. By that time, I’d gotten used to sitting with a girl. We even started whispering to each other a little when the teacher wasn’t looking. I had also figured out my desk, with all its hidden treasures. Believe it or not, the ballpoint pen was relatively new in the mid-nineteen-fifties, and fountain pens were still the standard. We mostly used pencils, but each desk contained a small inkwell for the more advanced student. I had a fountain pen for “special” writing. It contained a little bladder inside, and when you flipped a lever on the outside of the pen, it would siphon the ink from the well into a cartridge. Once the pen was filled, I could write elaborate letters, all beautifully adorned with large blobs of ink.

I have never forgotten those early days of learning. I guess in some circumstances, childhood experiences can leave a lasting effect on a person. I can still imagine the fine layer of chalk dust that covered everything, and how my nostrils would tickle from the faint aroma of wood smoke leaking from the cracks in the old wood stove. Mostly I recall the look and feel of the thick pages of our new red, yellow, and blue primers we were introduced to on the first day.

The blackboard was the centre of all things when I was a young student. Each morning, we’d arrive in the classroom as the teacher was putting the finishing touches on a chalkboard filled with printing. The assignment for one section of the five grades in the room may have been reproducing the words and paragraphs exactly as they appeared on the board. If you were in a higher grade, maybe the assignment was writing a story. Sometimes the board was filled with arithmetic problems to solve. For whatever reason, that blackboard was the main tool for conveying knowledge to our brains.

If it wasn’t the blackboard, the exercises were assigned through a series of workbooks. I remember very clearly my first new copy book: it was a small, soft-cover publication filled with solid and dashed lines. At the top of each page was a series of printed letters and words. Our job was to reproduce each letter exactly as it was displayed on the top line. Later on, as the copy books got more sophisticated, the printed letters gave way to cursive writing. We spent many hours meticulously reproducing the curly letters of each copy book. I only wish my writing today were half as legible as it was in elementary school.

Another common exercise was memorizing multiplication tables. In those days, every scribbler had the multiplication tables (up to twelve) written on the back cover. That set of tables has been forever burned into my brain. I am willing to bet that anyone who has had the pleasure of spending a year or two reciting the “times tables,” can still regurgitate a quick answer to any multiplication question…as long as it isn’t higher than twelve.

When printing, writing, or arithmetic were not the topics being covered, we were most likely reading. I started out my reading life with a very familiar family. On my first day of school, I was introduced to Dick, Jane, Sally, their pets Spot and Puff, and a teddy bear named Tim. They had parents with no names—known only as Mother and Father—and they didn’t have a surname. Sometimes they played with their friends, Tom and Susan, who also had no last names. Looking back, I can only remember, that those storybook kids grew up in the ultimate wasp family: the most idyllic of nuclear families. As we all know, most families aren’t that way and I, for one, am happy to see more realistic versions of families in today’s children’s literature.

Not every lesson in my early days of learning came from books or blackboards, though. Some were life lessons.

A wood stove in each room heated our schoolhouse, and the fuel supply was entirely the responsibility of the families with students attending the school. Each morning, certain students had to bring a few pieces of wood to the classroom. It was just one more frustrating moment for my poor mother on busy mornings. It was always at the last moment when one of my siblings announced that it was his turn to bring firewood to class. The amount of wood was obviously calculated carefully enough that the necessary supply was delivered but the school wood shed never overflowed.

In addition to supplying firewood, one student was chosen each week to deliver kindling and actually get the fire started. That task was usually assigned to one of the older students and, as a newbie, I didn’t have to worry about that detail. There are so many things about that old wood stove I still remember: one minute the thing was so hot the sides would turn red, while other times we’d all be sneaking to the cloak room to fetch a pair of mittens. If the temperature wasn’t an issue, the room was probably filled with smoke.To keep the fire going, we had to stoke it regularly, usually with an old broom handle.

That broom handle had multiple uses—sometimes as a disciplinary tool. In my younger school life, when a pupil got out of line, a leather strap was the tool of choice for punishment. However, it was not uncommon for a few delinquent students to return home at the end of a day with unmistakable soot marks on the palms of their hands.

Our little two-room school didn’t have any of the luxuries of today’s institutions. For example, we had no indoor plumbing. Our schoolhouse was the proud owner of a two-room outhouse, situated out back next to the cemetery fence. The girls used one side and the boys the other; the blue-ass flies had full use of the whole facility. Our outhouse was used for its designed purpose most of the time, but other times it hosted more undesirable activities, like smoking. Often I would eagerly look on, as Joe Smith demonstrated to his underlings, how to roll the perfect cigarette.

As a school kid in the fifties, I was also exposed to the many new “cutting edge” health treatments. Who doesn’t remember those opaque blue, oddly shaped bottles of cod-liver oil? I now appreciate that the oil was rich in vitamin D (a necessity given the Newfoundland weather), but damn, it tasted awful! A few years after we were force-fed that elixir, they introduced cod-liver oil capsules; they were slightly better than the liquid, but I could still taste fish every time I burped.

The other indelible mark left on me from my early school experience was the test for the dreaded tuberculosis. Students were never warned about those traumatizing events in advance—our parents likely knew about the impending torture, but they never informed us. I just remember the medical professionals showing up at our school, roughly pulling up my sleeve, and scratching several gouges in my wrist. They then dropped some foul liquid on the wounds and slapped a bandage on it. We all returned home wearing those awful wrist-wraps, and were told to make sure they stayed dry. About a week later, they returned and checked their work. If the scratches were inflamed, it meant you might be a TB carrier and were sent off for a chest x-ray (usually aboard the visiting x-ray boat, the Christmas Seal).

If the scratches were not inflamed, you were deemed “at risk” and inoculated against the dreaded disease. That vaccination was both embarrassing and painful. I was hustled into a side room (the cloakroom), my pants were pulled down around my butt cheeks, and a nurse etched several deep scratches into my lower back. Those, too, were filled with a stinging liquid and a large plaster was taped over the injury. After an eternity, I was rewarded with the torturous experience of having the tape removed. I dare anyone who went through that exercise to say they were not only scarred physically, but emotionally by some of those early medical miracles.

Other (less dramatic) remedies available in the school first aid kit included tincture of iodine; an antiseptic used on every injury from a scratch to an axe wound. Today, iodine is water-based, but back then it was laced with alcohol and burned flesh like liquid fire. If your school was a little more sympathetic, they stocked another, more humane treatment. The alternative to iodine was almost always a product called Mercurochrome. When given a choice between the horrible iodine or the relatively painless Mercurochrome, there was no contest. That amazing antiseptic is no longer available because its main ingredient was the always-poisonous chemical, mercury.

Not everything revolved around torture at my school. Even though we could have, at any time, been subjected to the dreadful strap or made to stand in a corner with a stack of books balanced on our hands, the few good memories of my early school days have never left me. Top in my mind is the first few days of term when new books were handed out. There was a special routine when my siblings and I took them home that first night: our mother would go out to our little grocery store and bring back a large strip of brown wrapping paper. We wrapped each textbook cover carefully to prevent any future disaster or exterior contamination. It was only then that we would carefully print our names on the new homemade book jacket and stack them on our night-stand for the next day’s class.

The other feel-good experiences were not earth shattering. At the time, though, nothing made me feel better than being chosen by my teacher to perform some choice job in the classroom. Taking the chalkboard erasers outside to beat the dust from them made a little kid’s day more special, and the ultimate thrill was when you were hand picked to ring the bell to bring everyone inside. That bell was enormous. It didn’t seem overly large when the teacher waved it around, but the first time I held it, its bulk surprised me. The thing was forged from solid brass, and the clapper had been replaced by a hex nut dangling from a piece of haywire.

I can honestly say I never truly enjoyed being a student. I managed to finish grade nine before I reached legal quitting age. The minute that happened I left my book learning behind and went to work in my father’s logging business. It took nearly five years for me to have my fill of physical labour and return to the classroom. It’s ironic, considering my dislike for school, that I would make a living off being in front of a class of college students. My grown-up classroom career lasted thirty five years and I loved every minute of it.