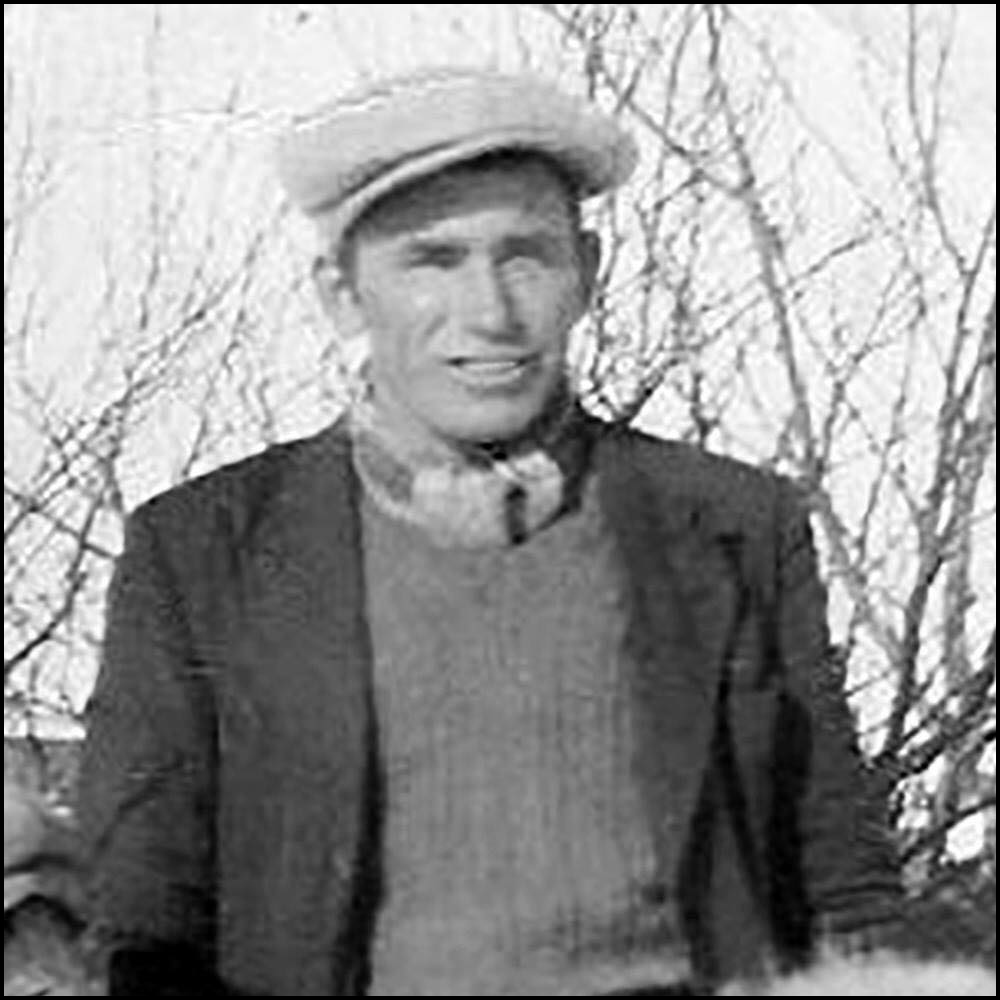

This is a story about my father and some of the things I still remember after all these years. He would be 110 years old if he were still around.

This is one of 52 stories in my book.

HANGING OUT WITH DAD

I’m the second youngest of ten children. I realize now that growing up in that situation was the greatest gift I could possibly have received. I didn’t appreciate it at the time, but being surrounded by so much love and camaraderie helped shape the person I have become. I didn’t see it as being all that great then; all I saw was severe competition for the attention of our parents. Wherever I went, whatever I did with Mom or Dad, there were several of my siblings, just a face-slap away. Because of the constant crowded conditions, it was always exhilarating to escape alone with my father. It wasn’t often, but when it happened, it burned memories that have always stayed with me.

I’m sure my brothers also got to be alone with our father a few times, and I do remember Dawson always going with him when there was mechanical work being done. Personally, I didn’t much go for hanging out on a cold day, trying to get some diesel engine started. I preferred to watch those goings-on from the warmth of our front window.

Some of my personal times with Dad were not necessarily earth-shattering, but to a little kid, it was everything. One day, he selected me to accompany him on a scouting expedition. In Newfoundland— unlike many other provinces where the timber rights are private—the right to cut logs was usually through a permit from the government. Residents would select an area where they wished to harvest wood, then acquire a permit. On that particular day, Dad was headed out to scout an area and mark off a perimeter.

Mom packed us a lunch and Dad and I set off in his pickup. After we parked the truck at our point of entry into the forest, Dad threw his lunch sack on his back and retrieved his rifle from behind the seat. It was not always necessary to have a gun in the woods, but I believe he was hoping to cross paths with a moose. We walked for what seemed like hours before we stopped to make a fire and have lunch. In Newfoundland, lunch is not really “lunch”; it’s more of a mid-morning snack.

Very few activities compare to the joy of “boiling up” in the wilderness. The standard procedure for making a campfire was simple: find an area away from any dry brush and clear a spot down to the dirt. Arrange a few stones in your cleared spot, spaced strategically to balance a fry pan. Finally, drive a couple of Y-shaped alders into the ground so a long stick could be laid across them. That contraption was perfect for hanging a homemade kettle (a large fruit can with a loop of snare wire attached).

During our morning snack, dad regaled me with his adventures. We had spotted some bear tracks and I was a little worried. He assured me that bears in Newfoundland were harmless, and if the bear saw you before you saw the bear, you would never see the bear. That was when he told me a story about the time he had killed a bear with a stick. Apparently he had been scouting timber, just like we were that day. He had left his lunch bag and rifle at his campsite and was doing a little reconnaissance close by. When he returned, a bear had its head buried deep in Dad’s food supply. He couldn’t get to the gun, so he picked up a stick to scare him away and hit the bear on the side of its head. He was flabbergasted when the bear keeled over. I have never forgotten that story, and I’ve always pictured my father as some reincarnation of Daniel Boone.

That scouting trip was also the day he let me shoot his rifle for the first time. Dad owned an antique gun from the Boer War. That war, in the late 1800s, was between the United Kingdom and the South African Republic. Newfoundland, being a British colony, was actively involved. We really didn’t know the name of the gun, but I have since researched it and concluded it was a Lee-Metford. Our father couldn’t get the proper bullets for it, but he figured out that 45-70 ammunition worked just fine. (0.45 was the diameter of the bullet in inches, and 70 was the weight of the powder in grains.) Anyway, that old rifle was so true Dad could hit any target, at what seemed like any distance. He explained to me that the bullets were just a hair too fat for the barrel and the lead got squeezed a little tighter on its passage through to tube. For whatever reason, the old Lee-Metford was the weapon of choice when anyone in our family went moose hunting.

Dad did explain that even his old rifle was not always perfect, and the gun was only as good as the shooter. He told me an amazing tale of the time he was tracking a moose in dense woods. He knew he was close to the animal because he could smell its musky odour. When he broke into a clearing from the thick brush, the moose was rearing right in front of him, its front legs stretching out above my father’s head. Dad told me he fired point-blank into the belly of the brute. That exchange resulted in man and moose each retreating at a mad dash in opposite directions. It appeared that, even at close range, my father completely missed his prize.

One of the many woods-related things I learned from Dad was that the birch tree supplied a number of necessities: birchbark was probably the best fire-starting fuel on the planet, its sap could also be consumed just like maple sap, and a horrible tea could be steeped from the small twigs at the end of a branch. Another valuable lesson I learned from him on our stomp through the forest was how to use trees to direct you safely back to your starting point. I was informed that the tops of several evergreen trees always pointed towards the sunrise. He said it was like your own little compass, always directing you home. Those trees were poor choices for Christmas trees, however, because your star always had a little tilt.

Dad rarely got his directions mixed up when traveling in the forest, and most of the time, he knew exactly where we were. On that particular day, though, he had a compass with him. We set out walking, Dad with his rifle on his back, me with the lunch bag on mine. After a period, he realized we had passed the same tree a couple of times. Recognizing his error right away, he came to the conclusion that the gun on his shoulder was affecting the compass in his hand. It was the last time I saw the compass that day. We spent most of the day trudging through swamps, thick forest, and some prime timber stands. I was starting to worry about getting out of the woods before nightfall and he responded reassuringly, “Don’t worry b’y, the truck is right there.” We took about ten more steps and broke into the clearing where we had parked.

Another great adventure I enjoyed a few times with my father was when I got invited on one of his drives into Grand Falls. Dad visited regularly; sometimes to acquire a new vehicle, but mostly to get a car or truck serviced at Eastern Motors. I would hang around the showroom and sit in all the new models. Sometimes, if we had a lot of time to kill, Dad would take a new car out for a test run. Usually, it was when he had errands to run and needed a vehicle to get around town. He had bought enough automobiles in that place that they were sure he would eventually buy a new one, so giving him a car to test drive, was a reasonable gamble.

One of my favourite jaunts, when we were in Grand Falls, was going to Lee’s Restaurant for lunch. Lee’s was a Chinese Restaurant, but for some reason, the only thing I remember eating there was a hot roast beef sandwich. It was so tasty at the time, but looking back, it was probably over-salted canned gravy. I remember it fondly, though—a great comfort food. Dad would always engage in friendly banter with the proprietor, and some of the verbal jabs and jokes have stayed with me. One ongoing exchange related to the rabbit soup. My father would always enquire where Lee got his rabbits when they were out of season. Lee’s response was always the same: “There’s always lots of rabbits around, Jim. There goes one now,” he would say, pointing out the window to a cat in the parking lot. It was a long-running joke between the two of them.

When we didn’t get out for lunch in Grand Falls, Dad would get creative. Sometimes on our way home, he would pull off the highway and find interesting spots to eat. None were more interesting and delicious than when we would stop at a pulpwood harvesting operation and eat in the cookhouse. I don’t know if Dad ever paid for those meals. Maybe, because he was well known, they fed us for free. Maybe he paid the cook on the side. Whatever deal they had negotiated, I enjoyed some of the most delicious meals I ever had as a kid. There was always a smattering of everything: chicken and beef, offered up with a great assortment of vegetables…mostly overcooked, but delicious. In those woods camps, baked beans were a part of every meal. A few years later in my late teens, I would end up working in one of those camps and enjoyed a helping of baked beans nearly every day.

Being one of five boys in our family, it was always a thrill to be alone with a parent. I always felt close to my father but I really don’t know how he felt about our time together. In all our interactions, I never saw him express a lot of outward affection for my brothers and me. Mostly, he was either joking in a “good old boy” fashion or disciplining us. I think that’s what was expected at the time. I sincerely believe a father showing affection for his sons was disapproved of in the 1950s; I have heard my sisters say he was completely different when interacting with them. I am absolutely certain our father cherished all his kids more than anything…it was just not outwardly demonstrated.

Case in point: one time after returning home from college for the summer, I walked into our house… right into a conversation Dad was having with a couple of men I didn’t recognize. I didn’t get introduced and I didn’t offer up my name but joined in anyway. After a few minutes, I excused myself and left to visit one of my brothers. Outside the door, as I was putting on my boots, my father started to heap enthusiastic praise on me. In my short absence, I apparently got introduced, a full detailed account of what I was studying, and what I hoped to become, was relayed to his company. If I had not dawdled outside the entrance, I would have never known that he was actually aware of or cared about what I was doing with my life. I am sure he took notice of all of my siblings’ lives as well, he just never offered up his praise to our faces.

I’m certain I am not a better father to my kids than Dad was to us. However, I have always made sure that I am very expressive of how proud I am, and how much I care for everything they do in their lives.